They found out why.

The men later authored a book titled: "Enough: Why the World's Poorest Starve in an Age of Plenty." The following is a chapter taken out of their book, under the title: "Who's Aiding Whom?"

Quotes:

Enough: Why the World's Poorest Starve in an Age of Plenty"You hear people say they don't care whether it rains in Ethiopia as long as it rains in Iowa..."

"They consider it their right to get food aid," he said, "whether they are starving or not."

"We need food aid to get rid of our excess commodities," explained Jim Evans from his cab atop a wheat combine near the Idaho-Washington border. "Food aid has huge impact on farms here,: Evans said. "Without the business, I might have to get a job at Wal-Mart."

"American farmers have a market in Ethiopia, but we don't have a market in Ethiopia," -- Kedir Geleto, Nazareth, Ethiopia.

By Roger Thurow, Scott Kilman

Who's Aiding Whom?

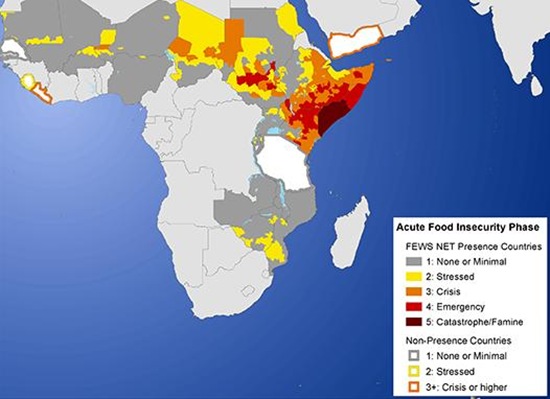

Ethiopian-grown grain accumulates in a warehouse in 2003 while food aid rushed into the country. The markets failed before the weather did. Image by Roger Thurow. Ethiopia

The main road to Nazareth is paved with good intentions. It begins at the port of Djibouti on the Gulf of Aden and runs west through the Afar Desert, past the ancient sands where the bones of our hominid ancestor "Lucy" were found, and finally along the Awash River basin up to the Rift Valley highlands and on to Addis Ababa. In times of great hunger, this is the road that brings relief to Ethiopia. Over the years, millions of tons of grain grown by American farmers, and the good intentions that travel with them-- to feed starving Ethiopians while helping U.S. agriculture-- have made this journey.

There is a second, less-traveled, road to Nazareth. This one shoots up from the south, from the Arsi and Bale regions where Chombe Seyoum's family has long farmed. In good years, when the rains generously sprinkle the highlands, caravans of trucks make the trek north laden with the bounty of Ethiopia's wheat and corn farmers.

The two roads meet in the center of Nazareth, in a cacophonous cluster of unbridled commerce: market stalls, bus stops, outdoor restaurants, transit hotels, and chicken and goat auctions. During 2003, as trucks piled high with food came speeding into that intersection from both directions, there was a spectacular collision: The mythology of American food aid ran smack into the reality of African agriculture, where hunger and plenty, shortage and surplus, sometimes exist side by side in the same country in the same year.

Jerman Amente, a thirty-nine-year-old Ethiopian farmer and grain trader, had roadside view of the collision. Standing in the dirt parking lot outside his grain warehouse, he could feel the trucks rumbling in from Djibouti, massive double-load wagons stacked to the top worth 220-pound white woven plastic bags bearing the characteristic red, white, and blue markings of American food intended for starving foreigners. The trucks came in waves, carrying in all more than 1 million tons of wheat, corn, beans, peas, and lentils from the United States. The ground shook as they rolled over the potholes.

Jerman shook with anger whenever he saw those trucks, for inside his warehouse, a vast concrete cavern, was an astonishing sight in a country then suffering from epic hunger: bag upon bag of Ethiopian wheat, corn, beans, peas, and lentils stacked in towering columns stretching toward the ceiling. This was what Chombe and Sasakawa's Tekle Gebre wanted everyone to see. It was the bounty from the two seasons before, the bumper crop from Jerman's farm and from the fields of his neighbors in Arsi and Bale and the grain-growing regions out west. This was the fruit of Sasakawa and Borlaug's effort to introduce farming methods that would boost production. These crops were also preserved in white sacks, though they bore the green, yellow, and red striped of Ethiopia. While American-grown food poured into the country, the homegrown Ethiopian surplus languished untouched.

Jerman, a short, wiry, energetic man, scrambled to the summit of one of his mountains of grain and comically posed for pictures. "I should hold a sign saying, "please send food. In Ethiopia we have no food!"He howled wickedly. "I don't think Americans can imagine this."

No, in 2003, Americans imagined their food aid arriving to save the day amid blighted landscapes of misery where everything was brown, dying, and grim. Their perception of the situation-- and of their own best intentions-- were perhaps most clearly expressed on one of the trucks that rolled up to the Ethiopian government's strategic grain storehouse in Nazareth, groaning under the weight of American wheat and corn to be unloaded there. The truck's passenger-side window had been converted into a stained-glass paining of Jesus. It was perfect imagery: Jesus, in Nazareth, bringing salvation to the Ethiopians.

Americans certainly didn't imagine their food aid arriving in green fields, rolling past warehouses full of local food. They didn't imagine African countries producing grain surpluses, certainly not those countries with all those starving people. And they certainly didn't imagine their aid being welcome by bitter sarcasm from the local farmers.

"American farmers have a market in Ethiopia, but we don't have a market in Ethiopia," huffed Kedir Geleto, who managed a grain-trading operation in Nazareth. Kedir, with Jerman, led a tour of their warehouses in Nazareth, just off the main road from Djibouti to Addis Ababa. Doing a quick inventory in their heads, they estimated that at least 100,000 metric tons of Ethiopian-grown grain, beans, and peas were idling here. And, they believed, there were another 50,000 tons stored elsewhere in the country. It was surplus food they hadn't sold the previous year, when prices had collapsed. They had held it in their warehouses to prevent prices and farmer incentive from plummeting even lower. And now, with nearly 2 million tons of international food aid rushing into the country, the market was further undermined.

The two traders knew that their grain wasn't nearly enough to feed all of their countrymen, and, as Ethiopians, they were grateful for the international food aid. "We really appreciate it," said Jerman. Yet as farmers and businessmen, he and many of his colleagues were also disgusted and discouraged.

Jerman reported that some farmers hauling their own grain up from the south, hoping to sell it on the markets, had pulled a U-turn in Nazareth when they met the food-aid trucks coming in from the east. They returned to their farms and stashed the grain in flimsy storage facilities, breezy bins open to the elements, where insects and pests and the heat would ruin it in a matter of months. What kind of incentive was this for farmers to improve their harvests? With food aid flooding into the country, what was the use of producing a surplus?

"We don't oppose food aid. When there's a deficit in the country, of course we need it. But when there's plenty of food in some part of the country, then it's unbelievable," said Bulbula Tulle, Chombe's neighbor who had his own storehouse in Nazareth.

..... to be continued.....